I got about fifteen pages into “Desiring God,” by John Piper last night before I got sidetracked. Piper and I have studied–and been influenced by–the same man, but for very different reasons.

Blaise Pascal was a prodigy mathematician that lived in 17th century France. His thoughts influenced many of our modern branches of practical mathematics. His work in probability theory influenced how we think about modern economics and social studies. He was also one of the first people to invent a mechanical calculator. He lived an incredible life, albeit a short one–he died before he turned 40. I undoubtedly use principles he discovered every day even without thinking about it (I work as a sales analyst) as do countless others.

What I did not know about Pascal was that he was also a Catholic theologian, and a key proponent of the idea of Christian Hedonism, which is the main thrust of John Piper’s entire life’s work.

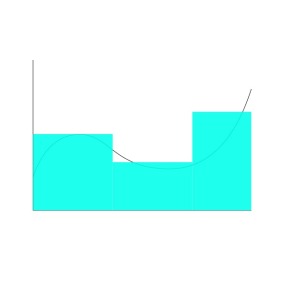

Hedonism by itself sounds sinful, and in most contexts it could be. It is the pursuit of pleasure through satisfaction of urges. In fact, when most people talk about self-control, that is exactly the type of thing that they’re trying to avoid. Theological Legalism is the implementation of divine “laws” to curb unbecoming and lustful appetites and behaviors.

The phrase “Christian Hedonism,” therefore, sounds counterintuitive at best, and oxymoronic at worst. At first glance, don’t those two terms seem opposed? Don’t they seem mutually exclusive? How can one hope to be a good Christian, and also pursue satisfying pleasures? The word “urge” even sounds sinful.

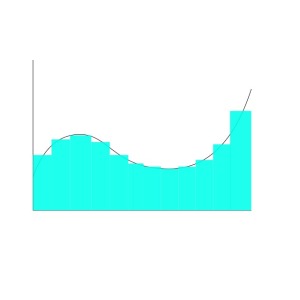

The answer seems obvious once it’s laid out in front of you: that satisfaction and pleasure can be derived in God. Piper quotes “Pascal’s Pensees” in Chapter 1:

“All men seek happiness. This is without exception. Whatever different means they employ, they all tend to this end. The cause of some going to war, and of others avoiding it, is the same desire in both, attended with different views. The will never takes the least step but to this object. This is the motive of every action of every man, even of those who hang themselves.”

(As a side note, it appears Pascal probably felt the same way about altruism as I do: there is no such thing as pure human altruism if part of the reason someone is being altruistic is to feel happy. He argues that literally every action we take is our will exerting its desire for happiness.)

One common reason that people say they turn to God is that they feel a void in their life. Feeling unrest, feeling unhappiness, and feeling anxiety are all symptomatic of the same thing–they are different ways of expressing that something indescribable is missing from a life. My best friend (who is my brother in every way but parentage) and I often discuss feeling this void, or feeling the symptoms of it. That well feels infinitely deep and infinitely wide, and the problem feels impossible to solve sometimes.

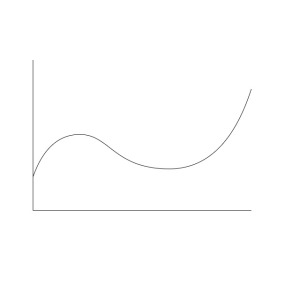

Pascal’s argument hits this problem exactly on the nose: Our soul’s main pursuit is happiness, and in doing so we are constantly trying to fill an infinite void. There is only one thing, he says, that can fill an infinite void: the infinite Himself.

“There once was in man a true happiness of which now remain to him only the mark and empty trace, which he in vain tries to fill from all his surroundings, seeking from things absent the help he does not obtain in things present. But these are all inadequate, because the infinite abyss can only be filled by an infinite and immutable object, that is to say, only by God Himself.”

If you have a twenty-thousand-gallon swimming pool, you’re going to need 20,000 gallons of water to fill it. If you have an infinitely deep hole in your heart, in order to fill it you’ll need another infinity. Like I said, the answer seems obvious when it’s laid out in front of you by a mathematician.